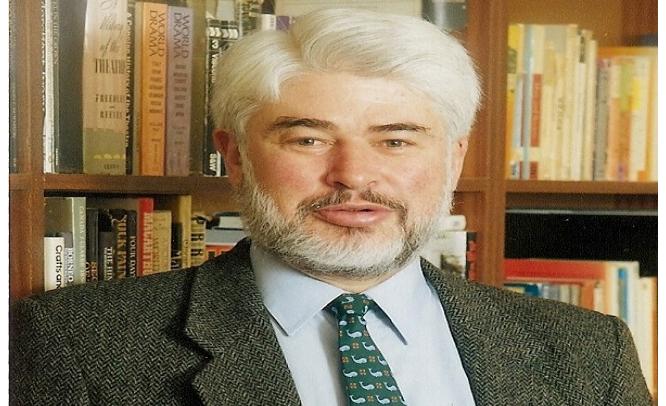

Change political mindset to overcome economic constraints, says John Kane-Berman, CEO, Institute of Race Relations

Miriam Mannak

November 5,2014:It hasn’t been plain sailing for South Africa. Besides slipping on the World Bank’s Economic Freedom Index and the World Economic Forum’s Competitiveness Index, the International Monetary Fund presented a rather bleak economic outlook for Africa’s second largest economy. While there are reasons to worry, analyst John Kane-Berman says the situation is not irreversible.

The year has been a tumultuous one for Africa’s southernmost nation state. Apart from being overtaken by oil producer Nigeria in terms of the size of the economy, South Africa is struggling subjected to various social and economic problems. The chronic energy issues for instance, which date back to 2008, have been far from solved and remain concerns for growth and competitive rankings.

Then there is the unemployment rate, which at 26% is the third highest in the world. Joblessness among youths in particular is problematic: South Africans between 16 and 35 account for some 70% of those without work. Other economic hurdles include frequent and often violent strikes; rigid and inflexible labour laws; overly powerful trade unions; the impact of ageing and ailing infrastructure such as the looming collapse of the water supply network; and a weakened and volatile rand.

Strangling the economy

In the meantime, the world’s largest platinum producer has slid on various international benchmarks, including the most recent Global Competitiveness Index by the World Economic Forum (WEF). South Africa’s dropped three places this year. Whilst this might not seem significant, the country’s loss on this particular index over the past decade amounts to 15 places – a 26% decline since 2004.

Analyst John Kane-Berman attributes the issues and challenges mentioned above to the manner policy is and has been made since 1994, the year of the first democratic elections. The CEO of the Institute of Race Relations (IRR), a classically liberal think-tank that aims to provide solutions to drive investment and growth, feels that South Africa “doesn’t need international reports and ratings to find out that the state is slowly strangling the economy.”

One of the things that concern him the most is the declined interest of investors. “The IRR has been involved in educating investors about South Africa’s benefits and risks for years,” he says. “In the last few weeks, one tour to South Africa was cancelled because the potential investors were no longer interested. Another local bank had to pack an investors’ meeting with its own staff because so few foreigners were interested. Even some of our own companies are seeking to reduce their exposure to South Africa.”

The tide can turn

This scenario is precarious, but not irreversible, Kane-Berman says. Turning the tide is possible, but it requires new policies based on a brand new ideology. It basically means that South Africa should steer away from wanting to be a revolutionary, interventionist state which has control over everything.

Kane-Berman: “Instead of wanting to interfere in every segment of society and the economy, the government should opt for liberal, less controlling policies. When the previous government handed over power to the present one, the IIR said the alternative to apartheid should be a free society built on the rule of law; one built on individual rights and responsibilities; free markets and enterprise – one where there is no distinction between economic and political freedom.”

This has not happened and can be considered one of the reasons why South Africa is lagging behind many other African countries in terms of economic growth. This month, the IMF’s latest World Economic Outlook update slashed the South African growth prospects for 2014 to 1.7% – down from an initial 2.3% forecast. Ghana and Cameroon, both middle-income countries, will see their economies grow by 4.5% and 5.1% respectively whilst the economy of copper producer Zambia is expected to rise by 6.5%.

Growth to fight inequality

It is South Africa’s third consecutive IMF downgrade in a year. Culprits include excessive red tape for entrepreneurs, rigid labour laws, labour instability and energy supply constraints. Kane-Berman says that little or no growth is detrimental to the country’s fight against inequality. He refers to the fact that South Africa, according to the World Bank’s Gini Index, is the most unequal society in the world.

The analyst adds that fighting inequality is futile under the current policies – namely the reduction of inequality through the redistribution of assets and under the transformational banner ‘Black Economic Empowerment’. “Talk jobs, not transformation,” Kane-Berman says. “Unemployment is the biggest cause of inequality. The only way to deal with unemployment, thus inequality, is much faster rates of economic growth. This requires higher rates of investment.”

“To get higher rates of investment, we need to secure property rights, lower the taxes, liberalised our labour laws, aim for privatisation, appoint a public sector based on merit, allow for free trade, get a professional police force as well as a more accountable parliamentary system.”

These and other proposed recommendations are incorporated in Kane-Berman’s 12-point plan, which he presented last year. The suggestions include turning economic growth into the state’s overriding priority instead of one of many as well as outlawing violent strikes and limiting red tape when it comes to setting up and running a business.

Change will happen

The plan also includes recommendations in terms of liberalising trade, decentralising government and policing, and privatising money-devouring state-owned enterprises such as South African Airlines. “Our government would rather have a failing state-owned airline than a successful privately-owned airline,” Kane-Berman says, pointing at SAA’s request to be bailed out – barely two years after it was granted £277 million in loan guarantees.

The IRR leader however, adds that he is confident that change will happen sooner or later, and that it might not come from the ruling party. “Change will come about, here as well as elsewhere – through the interplay between events and ideas,” Kane-Berman says. “Politicians can sometimes control events, but sometimes they can’t. Moreover, political parties can change quite radically. One must therefore look to ruling parties as much as to their opponents for political change.”

More Stories:

The grim and costly side of South Africa’s strike culture

Rainbow Nation’s energy sector is getting greener

Another view:

Why you should be bullish on Africa

Also read: