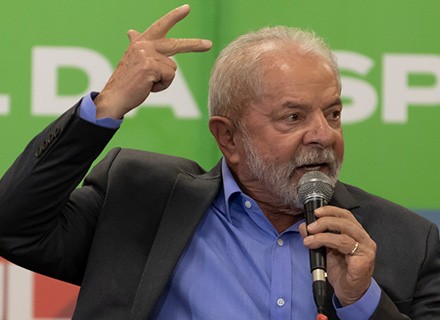

It is one of the most remarkable comebacks in modern history. Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, a popular but divisive former president of Brazil, won a slim victory in the nation’s elections recently. The former union leader got 50.9% of the vote, while the far-right incumbent Jair Bolsonaro got only 49.1%.

The outcome ought to end a bitter and intensely divisive election year. Instead, it forced this 200 million-strong nation to wait anxiously to see how Bolsonaro would react. Last year, the former army captain and President said he would not accept defeat in these elections. In a well-known echo of what former US President Donald Trump said in the 2020 election, his campaign and supporters repeatedly said that Brazil’s electronic voting system is vulnerable to fraud but have never shown any proof. Due to Lula’s razor-thin election margin, long-standing concerns that Bolsonaro’s supporters will stage their rendition of the January 6 Capitol rebellion have become more acute.

Lula’s background

For around 30 years, Lula has been a household name in Brazil. Lula helped found the socialist Worker’s Party and won his first presidential election in 2002 after working as the head of a steelworkers union in Sao Paulo in the 1970s. Brazil boomed during his two years in office due to a rise in exports to China and the value of Brazilian commodities. The windfall contributed to the significant expansion of social programmes like Bolsa Familia, which gave low-income families direct cash transfers to guarantee their children’s attendance at school, further solidifying Lula’s support among the country’s poorer citizens.

Later, though, Lula’s reputation suffered a severe blow. First, his 2010 resignation had an 83% approval rating. Then, in 2017, federal prosecutors brought charges against the former leader as part of their investigation into a colossal corruption plot that they said began during his time in office. Lula was sentenced to almost ten years in prison for taking a lavish home as a bribe, which he has always denied as a political attack. (The judge who found him guilty became Bolsonaro’s minister of justice.)

In 2021, Brazil’s Supreme Court threw out Lula’s conviction because he didn’t get a fair trial. However, it meant that he could run against Bolsonaro again in 2022. The UN’s human rights council later upheld this decision. But Brazilians are still very divided about whether or not Lula is guilty. In a poll taken in September, 44% of people said that Lula’s conviction was fair, while 40% said it was unfair.

How does the Brazilian economy fare?

Brazil has the largest economy in Latin America and the tenth-largest economy globally. Three major eras can be distinguished in the country’s recent history: the period of economic stability, which laid the groundwork for economic growth; the period of change and the reduction of inequality; and the period of crisis, which has brought to light both the country’s potential and vulnerabilities. In 2018, after two years of economic turmoil and many government corruption scandals, voters chose the far-right Jair Bolsonaro to lead the country. It was a change from years of left-wing regimes.

Bolsonaro came to power with the promise to reform pensions, privatize state-run institutions, make tax cuts for corporations and the elite, cut ties with China (One of Brazil’s largest trading partners) and befriend the USA under Donald Trump. In addition, Bolsonaro’s massive deforestation drive was designed to improve the country’s GDP at the expense of alienating the EU and climate change activists.

Bolsonaro’s government tried to deal with the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the economy, as well as the high inflation and political uncertainty that followed Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022. According to recent estimates, this strategy has worked: inflation has been partially reduced, unemployment is decreasing, and GDP growth has resumed (albeit at a slow pace). However, high economic inequality, poverty, and food insecurity remain issues. To deal with them, the new government will need more money, and the recent rise in commodity prices, which has helped the economy, may only last for a while. Lula will inherit all the problems from his opposition.

Before the October 30 runoff, Jair Bolsonaro and Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva ran as economic saviors. Bolsonaro cited the Brazilian central bank’s October 7 outlook to back up his allegation. Brazil’s GDP will expand 2.7% this year, far faster than the US. In addition, the former President tweeted that Brazil’s unemployment rate fell more than 40 other countries in one year.

“What the PT Workers’ Party destroyed in peacetime, we rebuilt through a pandemic, drought, and global war,” Bolsonaro remarked. One Lula da Silva supporter noted that his leadership from 2003 to 2011 was also successful to the same degree. He added, “In eight years, Lula produced 15 million jobs. In 2003-2010, unemployment fell from 12.4% to 6.7%.”

Not just for the Brazilian population, the election campaign needs to be more precise and more consistent in terms of economic metrics. For instance, many people need clarification as to why energy prices and inflation are currently declining in Brazil while skyrocketing elsewhere.

One explanation is Bolsonaro’s pro-stimulus agenda. In addition, the Brazilian Congress just approved a relief scheme that the President had pushed for. As a result, reduced taxes are offered on various items, including gasoline, electricity, gas, telecommunications, and public transportation.

In addition, by the end of the year, the welfare benefits for millions of Brazilians who live in poverty will grow from USD 77 to USD 116 (or €78 to €117). Additionally, recipients will receive a bonus month’s salary for the entire year. Henrique Meirelles, a former finance minister of Brazil, called this “political spending masquerading as social policy.”

Living standards, food security, and economic growth

Brazil’s economy began recovering in 2021 and continues this year, with a 2.7% growth expected for 2022. As a result, most Brazilians are optimistic about their living standards. On the strength of this development and a new USD 7.6 billion aid plan to help poor Brazilians with inflation, 58% of Brazilian adults feel their standard of living is improving. In contrast, 22% say it’s worsening. These values are up from 2021 and similar to 2020.

However, there is food security, with 34% of Brazilians indicating they had trouble affording food in the last year due to rising prices. Bolsonaro has caused more Brazilians to go hungry than any other president in the preceding 15 years.

Despite Brazil’s unemployment rate falling to 9.1% this summer, 56% of Brazilians still say it’s a horrible time to find a job. However, almost 4/10 Brazilians find it easy to land a job. Nevertheless, Brazilians remain pessimistic about job prospects, although not as much as before Bolsonaro took office or after the 2014 economic catastrophe.

Brazil’s fiscal policy

Unemployment, food insecurity, inflation and an energy crisis are Lula’s inheritance. To make it worse, Bolsanoro has tied the government down, possibly as a move to curb corruption.

Brazil modified its constitution in 2016 to create a fiscal “ceiling” that limits annual growth in federal government spending to no more than the rate of inflation.

In recent years, financial markets have viewed the constitutional spending cap as Brazil’s main fiscal anchor. Still, politicians from all political parties criticize it as a budgetary constraint during economic crises.

Many economists believe that the expenditure cap’s credibility has been damaged by the half-dozen exclusions and revisions that Congress has introduced to the regulation under Bolsonaro.

Lula is against the spending cap. At a gathering of economists last month, he said, “If you’re responsible, you don’t need a spending cap.” However, many critics say it is hard to expect fiscal responsibility from a man accused of severe corruption.

The new President must make a constitutional amendment to adapt to the looming global economic crisis. A feat that can be extremely difficult as his party is far from an absolute majority.

The trouble ahead

Most world leaders will probably be happy to see Lula back. During his first term, Lula was a significant player in world politics and frequently acted as a middleman between rival western governments and non-Western nations. That could be beneficial when the need for diplomatic efforts to establish global cooperation on the climate crisis is growing more pressing. In addition, the newly elected President has committed to stopping deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon, which would significantly improve Brazil’s strained relations with the EU.

The economic figures Bolsonaro announced appear to have disappointed Austin Rating, a Brazilian credit rating service. According to Alex Agostini, chief economist of Brazil, the country’s development over the previous ten years has been “horrendous.” As an emerging market, Brazil should expand more quickly than wealthy industrialised nations.

Ranking among the top economies in the world, it is a reflection of the economic roller coaster journey over the last ten years. Brazil occupied the seventh spot from 2010 until 2014. Then, it fell to the 12th spot in 2020. According to Austin Rating, it failed to thirteenth place in 2021.

Heron Carlos do Carmo, an economist at the University of Sao Paulo is skeptical that Bolsonaro can use Brazil’s economic improvement as a political weapon. “Even though an improvement is typically attributed to the incumbent, it is not decisive in changing an election result,” he claimed.

The analyst told the Brazilian newspaper Folha de S.Paulo that the overall economic situation is still quite dire, with millions of people falling into poverty. Financial metrics, he claimed, are “fiction” for the mass of the population.

President Lula stated on Twitter that “33 million Brazilians don’t have enough to eat.” We removed Brazil from the list of countries with the worst hunger in the past. But hunger has returned.”

Many in Brasilia hope that Lula’s economic reforms will uplift the poor and hungry, reduce income inequality and set the nation on track to being the economic powerhouse of Latin America.