When people took to the streets in Egypt in 2011, they chanted about freedom and social justice, but also about bread. The cost of pantry staples had jumped because of the soaring prices of goods like wheat, stoking anger with President Hosni Mubarak.

More than a decade after the Arab Spring, global food prices are surging again. The food prices have already reached their highest level on record in early 2022, when the COVID-19 pandemic, bad weather, and climate crisis upended agriculture and jeopardized millions of people’s food security.

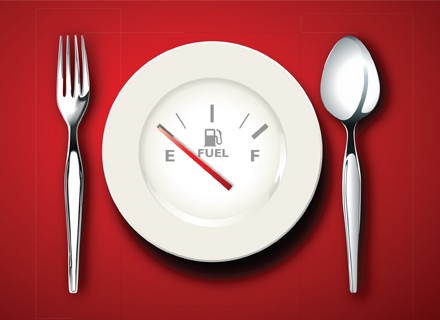

Also, Russia’s war in Ukraine had made the situation much worse by triggering a spike in the cost of the other daily necessity like fuel. It has also impacted the food supply chain. The higher labor cost, factory closures, and workforce shortages also drive up production and transportation expenses.

According to industry experts, cooking oil wholesale costs have skyrocketed, with up to a 30% increase projected in 2022. Other commodity expenses, such as dairy, fruit, and vegetables, are likely to rise as well.

At a time when labor expenses are rising, experts believe that the Russia-Ukraine war and the COVID pandemic put significant pressure on operator margins.

Rabah Arezki a Chief Economist of the World Bank’s Middle East and North Africa Region and a Senior Fellow at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government said rising food prices are extremely worrisome.

He also said that this could generate a wave of political instability, as people who were already frustrated with government leaders are pushed over the edge by rising costs.

The highlighted concerns by Arezki had come true as the world witnessed the recent unrest in Sri Lanka, Pakistan, and Peru.

In Sri Lanka, protests have erupted over gas and other basic necessities shortages. In Pakistan, double-digit inflation has weakened Prime Minister Imran Khan’s support, pushing him to resign. In recent anti-government rallies in Peru, at least six people have died as a result of increased fuel costs. The political strife is unlikely to be limited to these countries.

Hamish Kinnear, the Middle East and North Africa analyst at Verisk Maplecroft, a global risk consultancy said that the people have not yet felt the full impact of rising prices and that the world has to see much more.

Lessons from the Arab Spring

Food prices were skyrocketing in the run-up to the Arab Spring, which began in Tunisia in late 2010 and extended across the Middle East and North Africa in 2011.

The UN Food and Agriculture Organization’s Food Price Index reached 106.7 in 2010 and surged to 131.9 in 2011, setting a new high.

An Emirati commentator stated in January 2011, referring to the Tunisian street vendor Mohamed Bouazizi whose protest act sparked the Arab Spring said that Bouazizi did not set himself on fire because he could not vote but because he cannot watch his loved ones wither away slowly, not from grief, but from cold starvation.

Circumstances in individual countries differed, but the overall picture was obvious. The problem was exacerbated by rising wheat prices. And the food price issue has gotten significantly worse since then.

Global food costs have recently reached a new high. In March, the FAO Food Price Index reached 159.3, up nearly 13% from February.

The conflict in Ukraine, a major exporter of wheat, corn, and vegetable oils, as well as tough sanctions on Russia— a major producer of wheat and fertilizer—are projected to drive up prices in the coming months.

Gilbert Houngbo, head of the International Fund for Agricultural Development, said in April that 40% of wheat and corn exports from Ukraine go to the Middle East and Africa, which are already grappling with hunger issues, and where further food shortages or price increases could stoke social unrest.

The rise in energy prices is exacerbating the problem. Oil prices around the world are about 60% higher than they were in 2021. Coal and natural gas prices have also risen.

Many governments are struggling to protect their citizens, but the most vulnerable economies are those that borrowed excessively to get through the 2008 financial crisis and the COVID pandemic.

Arezki remarked that maintaining food and fuel subsidies will be tough as development slows, weakening their currencies and making debt payments more difficult, especially if prices continue to rise.

He said that the countries are indebted. They do not have buffers to deal with the tensions that will arise as a result of such high pricing. According to World Bank, about 60% of the world’s poorest countries were already in debt trouble or in significant danger of it.

Where tensions are simmering

Asia: In Sri Lanka, an island nation of 22 million, an economic and political crisis has already erupted, with demonstrators taking to the streets in defiance of curfews and government officials resigning en masse.

Sri Lanka was forced to deplete its foreign currency reserves as a result of high debt levels and a weak economy reliant on tourism.

This prevented the government from paying for essential imports like energy, resulting in severe shortages and forcing citizens to queue for hours for gasoline.

In order to try to secure a bailout from the International Monetary Fund, its officials have also devalued the Sri Lankan rupee. However, this step has just increased the country’s inflation. In January, it hit 14%, nearly double the rate of price rises in the United States.

Meanwhile, on April 9, Pakistan’s parliament passed a vote of no confidence against Prime Minister Imran Khan, ousting him from power and upending his government. While his political issues date back years, claims of economic mismanagement as the cost of food and fuel leaped, as well as the depletion of foreign exchange reserves which made matters worse.

The Middle East and Africa: Experts are also looking for signs of political unrest in other Middle Eastern countries that rely largely on food imports from the Black Sea region and frequently grant generous public subsidies.

Between 70% and 80% of imported wheat in Lebanon originates from Russia and Ukraine, where roughly three-quarters of the population was living in poverty last year as a result of political and economic collapse. The Beirut port explosion in 2020 also destroyed important grain storage.

Egypt, the world’s top buyer of wheat, is already feeling the strain of its massive bread subsidy scheme. After price spikes, the country has set a fixed price for unsubsidized bread and is attempting to secure wheat imports from India and Argentina instead.

With an estimated 70% of the world’s poor living in Africa, Arezki believes that the continent will be extremely susceptible to rising food and energy prices.

According to the International Committee of the Red Cross, droughts and violence in Ethiopia, Somalia, South Sudan, and Burkina Faso have created a food security crisis for more than a quarter of the continent’s population. It went on to say that the situation could worse in the coming months.

Political unrest has already begun to spread across the continent. Since the beginning of 2021, a succession of coups has occurred across West and Central Africa.

Europe: Even more developed economies, which have greater buffers to shield citizens from painful price increases, won’t have the tools to fully cushion the blow.

Thousands of demonstrators gathered in cities across Greece to demand higher pay to combat inflation. While France’s presidential election is narrowing as far-right contender Marine Le Pen plays up her plan to reduce the cost of living.

In April, President Emmanuel Macron’s government announced that it was considering giving food coupons to help middle- and low-income families eat.

Grocery prices impacted the United States

According to the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), grocery prices are expected to rise between 3% and 4% in the coming months. And that’s on top of all the other increases consumers faced over the past several months.

USDA said no food category will see a price decrease in 2023. All food categories, including meats, poultry, eggs, dairy products, fats and oils, and more, were amended upward by the USDA. Fresh veggies were the only category where the USDA made a reduction.

The most significant increase was in beef and veal, while the smallest was in fresh vegetables in 2022. In 2023, wholesale beef prices are expected to rise between 4% and 7%. Contributing to the higher retail poultry and egg prices, the report said, is avian influenza. Poultry prices are expected to rise by 6% to 7%, while egg prices are expected to rise by 2.5 % to 3.5%.

According to a report, an ongoing outbreak of highly pathogenic avian influenza could contribute to poultry and egg price increases through reduced supply or decreased prices through lowered international demand for US poultry products or eggs.

Retail prices for dairy goods are rising due to high demand. The USDA forecasts a 4% to 5% growth in dairy production in 2022. The invasion of Ukraine by Russia and interest rate hikes by the Federal Reserve are also exerting downward pressure on food prices.

The report said that the impacts of the conflict in Ukraine and the recent increases in interest rates by the Federal Reserve are expected to put upward and downward pressures on food prices, respectively. The situations will be closely monitored to assess the net impacts of these concurrent events on food prices as they unfold.

According to February’s US Consumer Price Index, released in March, the inflation came in at 7.9% for the last 12 months — the highest year-over-year increase since April 1981.

United Nation’s food price prediction

United Nations’ Food Price Index, which tracks monthly changes in international prices, averaged 125.7 points – a 28.1% increase over 2021.

FAO Senior Economist Abdolreza Abbassian explained that, normally, high prices are expected to ease as production increases to match demand. This time, however, the consistently high cost of inputs, the ongoing global pandemic, and ever more volatile climatic conditions “leaves little room for optimism about a return to more stable market conditions even in 2022″, he said.

At the end of 2021, world food prices fell slightly, as international prices for vegetable oils and sugar fell significantly, the data shows. The Food Price Index averaged 133.7 points, a 0.9% decline from November, but was still up 23% from the same month the year before. Only dairy posted a rise that month.

The Cereal Price Index also decreased 0.6%, for the full year, however, it reached its highest annual level since 2012, rising 27%. The biggest gainers were maize, up 44%, and wheat, gaining 31%. One of the world’s other key staple foods, rice, lost 4%.

The Vegetable Oil Price Index declined 3.3 percent in December, possibly due to concerns about the impact of increased COVID-19 cases, which have caused supply chain delays. The Oil Index hit a new high for the year, up 65.8% from 2020. Sugar, another important commodity, fell 3.1% last month from November to a five-month low.